Review of Denis Noble’s Dance to the Tune of Life

Dance to the Tune of Life by Denis Noble, 2017, Cambridge University Press

One of the grand mythologies of modern science is that of the persecution of Galileo.

Poor man: threatened with torture by the Inquisition for promoting the uncomfortable truth that the earth was not the center of the universe.

Oh, what struggles we men of science must endure!

What’s conveniently left out is that it was mainly Galileo’s clash with the prevailing scientific wisdom of the early Renaissance that did him in.

The Church in the 15th century was clinging to its relevance as the guardian of secular philosophical truth as well as religious truth, and it had embraced the astronomical theories of the authoritative and exhalted Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who had irrefutably proven that the earth, not the sun, was the center of the universe. Tycho’s math and scholarship were impeccable and widely praised. The fact that his conclusions also happened to align with the Church’s views cemented the case against Galileo. In its official denunciation of his work, the Church first cited his “foolish” contradiction of Brahe’s theories as perhaps a graver sin than his heretical interpretation of the Bible.

Who said Science and Religion can’t see eye to eye?

Trial of Galileo, 1633 (Italian School) Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Forgive my hyperbole, but we’re having a bit of a Galileo-Tycho Brahe moment today and, hopefully, no molecular biologists will be threatened with thumb screws.

The gene-centric theory of biological evolution that predominated through most of the 20th century, with its mathematical purity and cultural memes about DNA ‘blueprints,’ selfish genes, and genetic ‘programs,’ is now, like Tycho Brahe’s misconstrued universe, under serious threat by a whole lot of uncomfortable new experimental evidence.

Scientific revisioning happens all the time, but in this case the ‘science’ behind selfish gene ideology, and the Malthusian survival-of-the-fittest version of evolution it promotes, just happens to align with the most sacred presumptions of our techno-capitalist worldview: Greed is biologically justified; inheritance and evolution are reducible to lifeless algorithms; ruthless competition is “natural.” The almighty DNA-encoded gene is propped up at the center of our educational-cultural-political universe by scientific hubris and mainstream memetics, like a fat, self-satisfied toad on a log, and it’s going to take a lot of wise, articulate, courageous, and humbly brilliant later-day Galileos to knock it off.

One such hero is Denis Noble.

Dance to the Tune of Life updates Noble’s 2006 book, The Music of Life, in which he argued that life doesn’t emanate from some genetic program but from the dynamic interaction between different levels of biological organization – molecular to biochemical to cellular to tissue to whole organism – everything “dances” in harmony.

Here, he expands the narrative by introducing the concept of “biological relativity,” by which he means there is no “privileged level of causation in biology,” just as there is no fixed point in Einstein’s relativistic universe. Living organisms are “open systems … in which the behavior at any level depends on higher and lower levels and cannot be fully understood in isolation.” (160)

Noble knows what he’s about and writes lively prose with the easy grace and erudition of an Oxford don which, among many other things, he happens to be.

First and foremost, he is a biologist and philosopher of biology with a 50-year career in the lofty realms of British academia and scholarly research. He’s a former chair of cardiovascular physiology at the University of Oxford and has held distinguished faculty and research appointments at Oxford, Osaka University, Xi’an Jiatong University in China, the British Royal Medical Research Council, and the Canadian Medical Research Council. He’s published over 700 studies and reviews in leading research journals like Nature and Science. Among his many achievements, he helped establish the intellectual framework for systems biology, a discipline that’s now widely used in medical and pharmaceutical research. He also developed the first viable model of a working heart and, most recently, helped pioneer the ‘modern synthesis’ theory of evolution which uses evidence and insights from molecular biological research over the last three decades to revise and, to a certain extent, refute the traditional neo-Darwinian theory of evolution.

We learn that as a doctoral candidate in physiology in the 1960s, Noble set out to demonstrate how complex biological functions, like membrane ion channel regulation, could be reduced to computational models. There was no practical reason for doing this. The goal was to help bolster the prevailing belief (then and, unfortunately, also now) that all biological phenomena could be reduced to physics and math. Young Noble was a true believer and a whiz at using computation to solve complex models.

After some initial success, he came to realize that reducing biology to math is impossible, not because of the difficulty of accounting for all the variables and so forth, but because when you reach a certain level of biochemical complexity, novel biological phenomena ‘emerge.’ These emergent phenomena exert a ‘causative’ regulatory force on the biological structure they emerged from. The force can be measured and quantified, but it can’t be reduced to a simpler physical or mathematical model. It is what it is.

He cites the self-regulating Hodgkin Cycle as an example. Protein channels connecting the interior and exterior of a cell membrane create flows of ions that affect the voltage of the cell. In turn, the voltage of the cell controls the opening and closing of the protein channels. This phenomenon of a cyclical feedback loop arises purely from the functional organization of all the component biomolecules. It can only exist at the biochemical level.

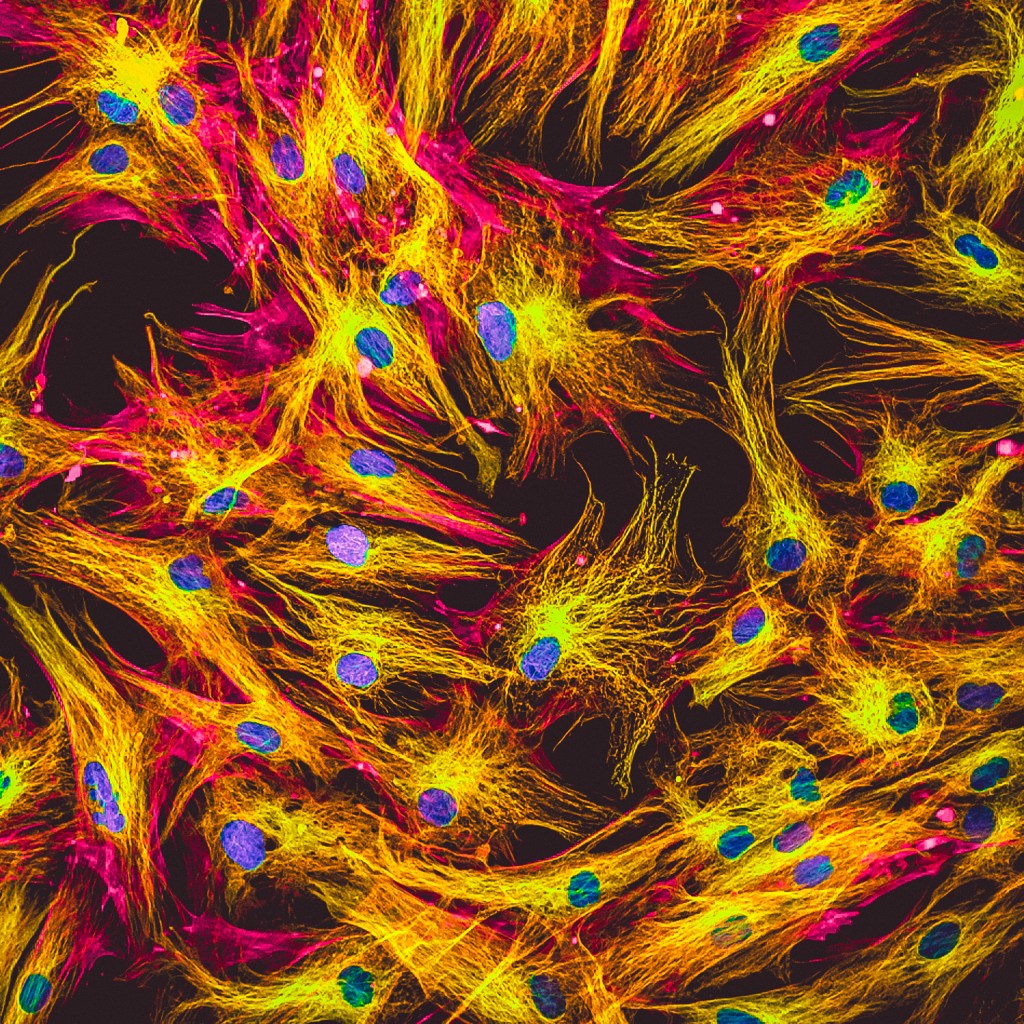

Fluorescent microscopy of human skin cells in culture, highlighting the cell nuclei (blue) and the actin (pink) and tubulin (green) protein filaments that provide structure and a means of transport within each cell. The membranes dividing the individual cells aren’t visible. (Vshivkova, Shutterstock)

More important, as Noble later realized, was that the ‘purpose’ of the protein-ion cycle imposes a downward organizing pressure on how all the component parts interact.

This nudged him towards his distinguished academic journey of formulating a systems approach for understanding how biological processes that occur on the molecular, cellular, tissue, and organism levels can be functionally interrelated.

What he gradually came to see was that the core dogma of 20th century genetics – that genes controlled protein synthesis which, in turn, gave the cell its structural and functional properties – was unlike other cellular-biomolecular processes. Entirely through the actions of the proteins they were synthesizing, genes (large matrices of DNA molecules) were supposedly regulating higher cellular functions in an ‘upward’ direction with no apparent feedback.

As experimental research accumulated over the second half of the 20th century, it slowly became clear to him that ‘downward’ forces from within the cell, oftentimes in response to environmental influences, did provide a kind of feedback by regulating how DNA was read and translated. It was also realized, by Noble and many others, that DNA sequences could be revised by RNA-driven responses and by horizontal gene transfers from other cells. The gene-DNA matrix played a crucial role in protein synthesis and cellular processes, but it was more correctly seen as part of an integrated and open system that responded to environmental influences and cellular dynamics. It was not the “selfish” ruler that neo-Darwinism held it to be. As Nobel prize winning biologist Barbara McClintock observed, the genome is merely an “organelle of the cell.” It’s not selfish, generous, thoughtful, or angry; it’s neither a program nor a blueprint. It doesn’t control anything. It’s just a functional and adaptable biochemical apparatus that plays an important role in the life of the cell, but by no means the master of the shop.

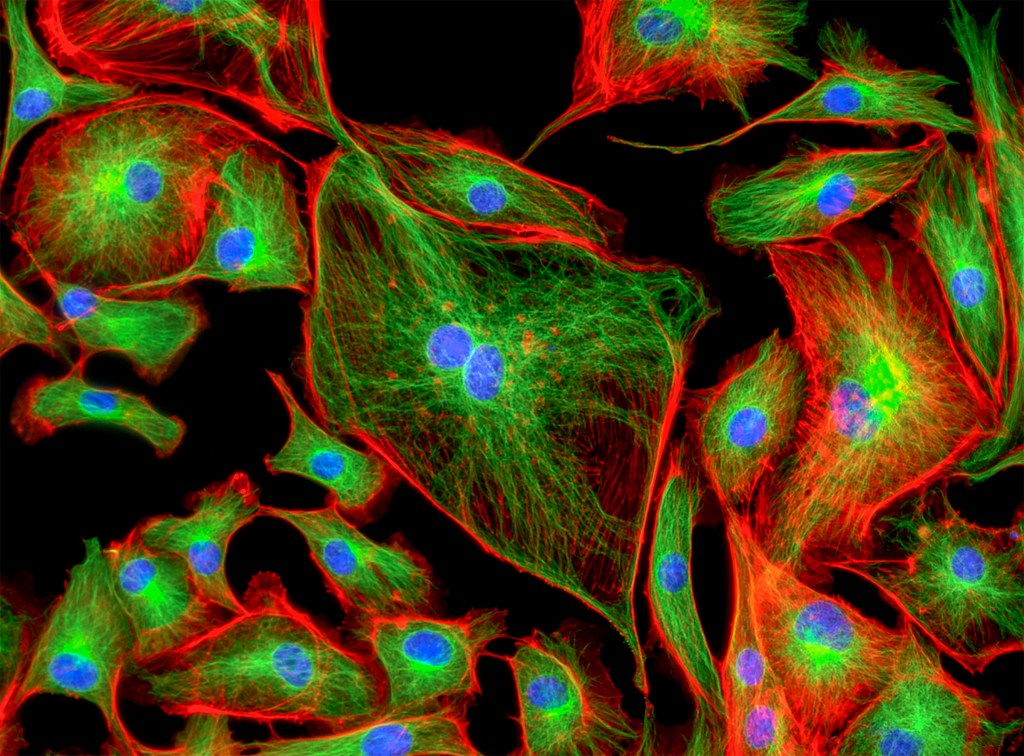

Flourescent microscopy of bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells highlighting the nuclei, actin filaments, and mitochondria. Novel biological phenomenon emerge when certain levels of complexity are reached that can’t be reduced to simpler models.

Like other ideological empires, the decline and fall of the selfish gene has happened (and is still happening) gradually, and Noble is by no means the only proselytizer of the new biology. Of the many authoritative books on the subject – some written for specialists, some for the public – I would say that Eva Jablonka and Marion J. Lamb’s Evolution in Four Dimensions (MIT Press, 2005) is perhaps the most comprehensive, but it’s a bit too wonky to recommend for non-biologists.

Noble covers the same ground but is more light footed and nimble. You also don’t get the same whiff of strident atheism you get in Jablonka and Lamb’s book, and many others as well. One of the concerns that biologists have raised about dethroning the old, gene-dominant paradigm is that it could breath new life into creationist and intelligent design versions of evolution that traditional neo-Darwinians had put to rest. If evolution is driven by random mutations in the genome – the prime directive of selfish genism – then how can there be any divine plan? Suggesting that something much more complex is going on opens the door to all kinds of messy, theistic shenanigans.

Noble handles this … nobly, by elaborating the point that scientists might not be as well equipped to address matters of faith as many presume to be. If the new evolution let’s God back into the conversation, what kind of God are we talking about? A spirit? A creator? Don’t scientists themselves often have “faith” in a creatively elaborate vision despite having little evidence to support it being true?

Say, for example, selfish gene theory?